- Home

- Eoin Dempsey

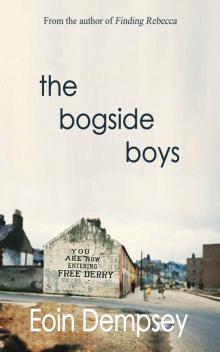

The Bogside Boys Page 7

The Bogside Boys Read online

Page 7

Mick pushed back the black gates of the City Cemetery and started up the hill. A rainbow arched over tranquil green hills across the river. Mick stopped for a few seconds, just to feel the breath rolling in and out of his lungs. The graves of the other victims of the march were heaped in flowers, bright, shining colors against the dark of the headstones, the gray of the sky. Relatives of the other victims said hello to him as he passed, people he’d never known before last week but who were now bound to him forever. They all knew the twins, the sons of Peter Doherty. People shook their heads as he walked by. His mere presence was enough to make grown men cry. He turned up the collar of his coat in a vain attempt to ward off the encroaching chill in the air, held up a hand to greet dozens of straggling mourners. Still he walked on, and the figure of his brother came into view.

Pat was standing over their father’s grave, smoking a cigarette, didn’t see Mick approaching, and didn’t turn as he stood beside him.

“Did you see Jimmy’s grave, and Noel’s?” Mick began.

“I did, aye.”

“Your boss came into the shop looking for you.” No answer came, so Mick spoke again. “He was wondering where you were.”

“I was here.”

“All day?”

“Aye.”

They stood in silence for a minute before Mick spoke again. “Should you be smoking, here?”

“Da doesn’t seem to object.”

“Did you tell Fergus that you weren’t coming in today…?”

“I was standing here praying. I’ve been praying most of the day. Have you ever heard of Saint Rita?”

“No, I can’t say I have.”

“She was one of Da’s favorites. She’s the patron saint of impossible causes. She seemed like the appropriate lady to pray to.”

“For what? What are you praying for exactly?”

“Justice.” He brought red eyes to his brother. “There’s no bringing him back but it’s up to us to make sure he didn’t die for nothing.”

“We’re leaving Derry,” Mick said reaching over to his brother. “Maybe that’s what Da died for, to give us the better life he always wanted for us.”

“So we could turn tail and run? Leave our people? I don’t think that’s what he died for, little brother.”

“You agreed to come to Paris, Pat.”

“Aye, I did, and I will, for now.”

Mick thought to tell him about the conversation he’d had with Melissa on Sunday night, about her coming to Paris eventually. Not here. Not now. Another minute or so passed. Neither man spoke, just stared at the words on the headstone as if they could unwrite them somehow.

“I think it’s best we get away while we still can.”

“I spoke to Paul last night.” His eyes were fixed on the grave as he spoke. “He’s off to begin training in a few days, around the time we run away to France.” He threw down the cigarette.

“That’s his choice.”

“And John too. A lot of boys from around here, a lot of boys who saw what happened, what happened to Da.”

“You said yourself, Pat. You said yourself that the police would deal with it.”

“I felt awful for that little girl the soldiers murdered last year, and the fifteen-year-old coming out of the chip shop after he got his first week’s pay. I felt awful, but it was a situation for other people to deal with.” He looked at Mick, straight in the eyes now. “Da always said, ‘“best not get involved boys, politics isn’t for us,”’ but where does that leave us now? How can we put our faith in the government, the same system that murdered our father?”

“What are we supposed to do? Take down the entire British Empire?”

“Something, Mick. We’re supposed to do something. Something to get justice for our father, something to protect our community, so no more Peter Dohertys or Jimmy Kellys or Noel Wrays have to die.”

“This whole house of cards is gonna come down anytime now, Pat. Free Derry isn’t going to last much longer. The Brits won’t stand for it. Who knows what’ll happen? We can be free in Paris. We can live the lives we should have been born into. There’s no jobs there solely for Protestants or Catholics, no restrictions on housing or voting dependent on what religion you happen to have been born into. We can be who we want to be there, be with who we want to be with.”

“Is that who this is about, that girl?”

“If you’re referring to Melissa, aye, yes, in part, but it’s also about our Ma. Her husband’s dead. She needs us.”

“You don’t think I know that? That’s why I agreed to go to Paris with her in the first place.”

“What are you planning, Pat?”

“I don’t know. I’m making it up as I go.” He reached into his pocket to fish out a pack of cigarettes, but didn’t open it, just stared at the writing, holding it in his hand. “I just wish I didn’t feel like this, all the time. I just wish I could get rid of this emptiness, this vacuum inside me. It’s like nothing I’ve ever known.”

“You were so strong those first few days.”

“I always was a good actor. I don’t remember any of it. The days between the march and the funeral are already gone. I barely remember the funeral itself.”

An elderly woman in a black shawl came to the graveside to lay a fresh wreath alongside the others. Mick prayed that she wouldn’t recognize them, wouldn’t try to offer some crumb of comfort. She looked up at them with a kind smile and ambled away. The rains began to come again, just a few drops, spitting down on them.

“You’re wrong, Pat. There’s an uncommon strength in you. That strength is what got this family through the last week. I don’t know how we could have done it without you.” No answer came. “I feel the same way as you do. I feel the same anger, the same frustration, but if the government inquiry uncovers the truth, then justice will be done. The soldiers who murdered Da will pay for what they did.”

“You believe that, do you?” It was Mick's turn not to answer now. “I didn’t think so. I know we’re different, but I’d hoped we wouldn’t be that different. I’d hoped you wouldn’t be that gullible to believe what they told you now.”

“Where do we go from here then, Pat?”

“What do ye mean?” The smoke billowed leaden clouds around him as the wind lifted.

“I mean what do we do, for justice for Da?”

“Well, they say living well is the best revenge. We can go to Paris, make lives for ourselves there, look after Ma into her old age. You can have your Melissa. No one there will care if she’s a Protestant.” His voice was flat. Mick had never seen him like this before, so devoid of joy. “We could have our lives there in peace. Paris isn’t perfect, but there’s no war there.”

“That doesn’t sound so bad.”

“If we do that, we desert our father, and our people. We leave our community in the worst place it’s ever been, like rats abandoning the sinking ship.”

“No one would think any the worse of us if we left.”

“I would. Wouldn’t you?”

Mick grimaced as the frustration bubbled up from within him. “Why are you asking me that? Why can’t you think about our mother?”

Pat ignored the questions. “You have Melissa to think of. How serious are you two?”

“Serious.”

“I told you I was praying to St. Rita.”

“Aye, ye did.”

“She’s the patron Saint of impossible causes. She lived in Italy five hundred years ago. She was married off at age twelve and had two sons. When the boys were about sixteen, their father, Rita’s husband, was killed in a local blood feud. Her sons swore revenge.” The rain thickened around them, and people began to put up black umbrellas. The boys didn’t move. “But Rita wouldn’t have any of it. Being the pious person she was, she tried to convince them to forgive the killer and even publically pardoned the murderer at her husband’s funeral.”

“So what happened?”

“They didn’t listen to her. They swore vengea

nce. Even after what their mother had said at the funeral, even after she begged them not to. So she prayed to God to stop them Himself.”

“Did He?”

“Well, yeah, He did. Before they had a chance to gain their vengeance, they died of dysentery. Both of them.”

“So God answered her prayers by giving them both dysentery?”

“It was an impossible cause. Dysentery saved their souls before they had a chance to commit the mortal sin of murder.”

“Do you think Ma is praying for something like that for us?”

“Dysentery? Nah, I’d say more like a nasty case of syphilis.”

“That would solve our problems, all right.”

“It’d certainly solve the problem of you falling for that Protestant girl, little brother.” A fleck of color returned to Pat’s voice, drawing a smile from his brother.

Mick looked at his watch. It was almost four o’clock. “Are you ready to leave? Do ye want to go for a pint on our way home?”

“Just give me a little while longer,” Pat replied. Neither spoke as they stood there for a few more minutes. Several men shook their hands and a woman even handed Pat a bouquet of fresh flowers as they turned to walk away. He placed them down on the grave of one of the other victims. Melissa appeared in Mick’s mind like an apparition, the picture faint. Nothing was going to be easy for them. The thought of letting her go was as jagged and painful as anything else he’d felt. They stopped into the first pub they came across on the way home. The conversation was almost normal. Pat seemed to be returning to some version of himself. When they arrived home, their mother had already packed most of her clothes into suitcases by the front door.

Chapter 9

The letters he sent were all she had of him now. It was surprising that her parents never questioned those letters with the Parisian postmark that arrived two and sometimes three times a week. She’d told her mother that Mick had moved away. It was easier not to lie. She was a terrible liar. The feelings she had for him had not dimmed, had not been diminished by the distance between them or the two months he’d been gone. She felt that he was with her all the time, and she with him, in all her thoughts and actions, as if they were one now, like the water in two separate streams, indistinguishable once joined together. Michael Doherty was the first thing that came to her as she awoke and the last thing that hushed her to sleep at night. Her mother was puzzled. Melissa hadn’t shown any sign of the heartbreak of a breakup. Melissa assured her that he was in Paris but neglected to mention her plans to travel there in the summer, neglected the plans they’d made for her to move there permanently the year after.

It was a sunny Tuesday in mid-April. Roger Dalton had taken to walking her home, at least as far as his house. None of the boys knew about Mick and only some of her girlfriends. Some of her friends thought the same way as their parents, voicing quiet disapproval, some did not. But it didn’t matter. Soon no one’s opinions about their relationship would matter except their own. Roger was a nice boy, good looking and fun. Melissa knew he wanted more, just pretended not to. It was easier that way, more polite. She said goodbye to Roger and her thoughts immediately turned to Michael. She smiled to herself as she ambled up the garden path towards the front door of her parent’s house. She pushed open the front door. Jenny was home from school already, and their mother was in the kitchen, the aroma of newly baked bread filling the house. The letter was on the hall side table. Mick’s messy handwriting brought a smile to her face and deepened the longing within her. It was a funny feeling; funny to be in love with someone you never saw. Melissa picked up the letter and slipped it into her bag before making her way upstairs to her room. She had a routine, a ritual for reading his letters. She sat up on the bed, took out the old shoebox she kept them in, took off the lid and opened the letter. She took the single sheet out of the envelope and lay on her back to read it.

Melissa,

Life in Paris is still good, although it would be much better were you here with me. I miss you every day. It’s a strange mixture of joy and pain that I feel when I think of you. But I remind myself that the future is ours, and now that we’ve found each other, that we have each other, our whole lives together are laid out in front of us. One day we’ll see each other so often that you’ll be sick of me! I’ll make our children tell you stupid jokes (in French accents, who knows?) and annoy you while you’re trying to concentrate on more important things. You think that’s funny right now, but just you wait!

Working in the shop is fine. I never thought I’d miss staring at the tops of men’s heads so much. I suppose I miss the feeling of my dad being there with me. I knew he was there with me in the shop. It’s different now. There’s no link to him here. He feels far away or even gone. Ma is okay. She’s keeping busy and enjoying the way of life that she grew up with. Grand-mère is fabulous. She is eternally sweet, completely wonderful. Grand-père, not so much, but he’s not such a bad old guy.

Pat is the problem. I miss my brother because the brother I see with me every day isn’t him. You must be sick of me telling you this, but it’s on my mind all the time. I don’t know what to do. He never smiles or laughs. He used to laugh all the time. He seems to have built Derry up in his mind to be heaven on earth. He talks about moving back there all the time. I could never let him do that alone.

I love you,

Mick

Melissa let the paper rest against her chin. She’d not voiced her opinion to Mick, but it was clear that Pat had only moved there as a temporary measure to moderate his family’s grief. A selfish flame of hope lit within her, but would they be better off back in Londonderry? Pat was still suffering. Was the path back to Londonderry a path to happiness or just the revenge that most of the Catholic boys who Mick had grown up with now sought through the medium of joining the IRA? If Pat joined, would Mick? Surely not, if only because of her and the love they shared. Surely he would value that above revenge or the false hope of ‘justice’ that the IRA recruiters spouted to willing throngs of young men with nothing but anger and disillusionment and pain seething through them. How had Mick checked his anger? Was it her? Was it the love he felt for her? Was she the reason he wasn’t succumbing to the same sickness that had seemingly taken hold of his twin brother?

*****

Patrick picked up the wooden crate of tomatoes and placed it on his shoulder. Grand-père gestured to him to put it in the corner. Grand-père didn’t speak any English, flat out refused to, and Pat’s French was short of where Grand-père expected it to be, so the two men rarely spoke, rarely even attempted it. Working helped. It was a way for Pat to escape himself and the thoughts that haunted him. But there was no real escape, even in sleep. The image of his father, dying on the pavement outside the Rossville Flats permeated every dream, holding dominion over all else. That was most nights, and how he awoke most mornings. They’d spoken about it many times, but Pat wasn’t healing, not like his brother was. Mick seemed to have some inner fortitude that Pat didn’t. It was hard to fathom. All their lives he’d been the big brother, the one to make the decisions, a born leader.

Mick was behind the counter trying to talk to a customer. Grand-père stood beside him, observing with judgmental eyes. The man thanked Mick, happy with the service. Grand-père shuffled away without a word. Pat sat on the crate of tomatoes, his weight on the corner so as not to bruise the fruit. Mick walked over and sat down on the floor beside him.

“What’ll the old man say about us knocking off work?” Pat said.

“Do you care? Whatever he’s thinking, he’ll get over it.” Mick looked at his watch. “The shop’s closing in ten minutes anyway. We’ll close up for him then.”

“How’s that wee girl o’ yours back home?”

“She’s doing great, still planning on coming over to see us here this summer.”

“Aye, right, sounds like fun. Going out with a Prod doesn’t matter here, nor should it.”

“A lot of things that matter back home don’t matt

er here.”

“That doesn’t mean they don’t matter though, Mick.”

“Aye, you’re right.”

They helped Grand-père close the shop. Mick brought in the vegetables from outside, stacking them in tidy rows at the back of the shop as Pat rolled up the awnings. It was a fine spring evening, the likes of which were all too rare in Derry. It was a beautiful evening to sit out in the sun, smoking a cigarette and drinking beer. Mick and Pat took off their aprons and sat at a table outside on the street. The street the shop was on was magnificent, a feast for the eyes, as was almost the entire city. The high buildings on each side of the road were stately, lending grandeur to the cobbled street below. Each shop window was sumptuously ornamented with fresh goods as if specifically chosen for their color, their beauty. But it was the people who were the truest adornment. Almost every person that passed was like a wonderful melody for the eyes, immaculately dressed as if wandering down a catwalk. Mick fixed his eyes on a gargoyle sitting atop the building across the street, and Pat sat down opposite him. With no rubble, no barricades or burnt out cars anywhere, it was hard to imagine these people had any idea what was going on just a few hundred miles away.

The narrow sidewalk provided enough room for the table and two chairs but little else. People walking past had to step one foot into the street as they passed, but the boys had long since stopped worrying about Parisians grumbling. They always seemed to have something to complain about.

Pat opened the beers as Mick lit up a cigarette and passed one across to his brother. People stared at them, the identical twins sitting together on the side of the street. It was normal. They boys were used to it.

“How are you doing?” Mick began, meaning each word in the question.

“I’m feeling guilty.”

“Guilty about what precisely?” Mick asked although he knew.

“Guilty about leaving our friends and family to deal with the Brits. Guilty that the likes of John and Paul have dedicated themselves to protecting our community and gaining justice for our father, not to mention Jimmy and Noel.” He pressed his lips hard together before opening them to speak again. “Honestly, I feel as if I’m wasting myself here, beautiful city that this is and all.”

The Bogside Boys

The Bogside Boys