- Home

- Eoin Dempsey

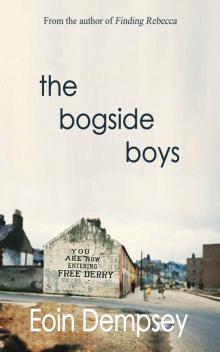

The Bogside Boys Page 9

The Bogside Boys Read online

Page 9

Neither brother spoke at all as McClean took the opportunity to give them another lecture on republican history. His voice was light as he spoke. He almost had the air of a storyteller, regaling them with mighty tales of ancient heroes. It was clear that he romanticized the histories in his mind, and the enthusiasm he had for them was infectious. He only stopped talking when they reached the border. He was pleasant and polite with the soldiers at the checkpoint. The boys got out of the car as the soldiers searched it, but there nothing to find but the light bags the boys had brought with them.

The terrain in Donegal was exactly the same; lush rolling hills pockmarked with stones. The roads were markedly different however, and the car bounced up and down through potholes in the road as they went. It was only the second time the boys had ever been over the border, and they peered out like children expecting to see some sign of the unusual freedoms the people of the south enjoyed.

They had driven half an hour past the village of Castlefinn before McClean pulled off the road to a farm, remote and private. He told them to stay put as he went inside, his feet crunching on the gravel path that led up to the large farmhouse. The farmhouse was old but well kept, freshly painted, with neat rows of flowers in front. Neither spoke for the two minutes that McClean was gone. He emerged from the farmhouse with a tall, elderly woman, perhaps seventy years old. She was wearing an old-fashioned shawl with long gray hair spilling over it. Her striking blue eyes bore testament to a beauty that had faded with time but a strength in her that remained. She strode toward the car. They both climbed out. McClean introduced the woman as Sorcha Uí Bhraonain. They both knew the name and stepped forward to greet her with a firm handshake. She gave them a friendly if serious look as she greeted them.

“Welcome to my home,” she began. “This has been a safe house in a republican stronghold since before even I was born. It was burned down by Black and Tans during the war of independence in reprisal for IRA activity in the area back in ’20. The Free State government executed my brother here during the Civil War, almost right where you’re standing. I saw it with my own eyes. This is where your training and initiation into the Provisional Irish Republican Army will take place. You will address me as Bean Uí Bhraonain.” Mick didn’t speak much Irish but knew that ‘Bean’, pronounced ban, was Irish for Mrs.

“Yes, Bean Uí Bhraonain,” they said in perfect synchronicity.

Sorcha smiled to McClean. “So they even speak together, do they?” McClean didn’t answer, just flashed a grin back.

“You will be here for several weeks until we feel that you’re ready for the field. You will train with the thirty-four other recruits we have here at the moment. Have you any questions?”

They didn’t, so they were directed to a large barn with rows of bunk beds lined along the side. Each bed was made perfectly. The boys left their bags on the spare bunks they found. McClean brought them out the back and up a narrow trail, surrounded by high, overgrown hedges. The three men walked in silence for ten minutes until they reached a clearing where the other volunteers were sitting in front of a chalkboard, listening to a lecture on gun safety. Each volunteer was dressed in green combat fatigues. The man giving the speech had a black beret on his head. He motioned them to sit down at the back. There were no introductions made. The volunteers turned to look at them as they sat, several doing a double take. The lecture was similar to what they’d heard in the previous weeks in their meetings with McClean, who’d slipped away after they’d sat down. Mick looked through the faces as best he could, some were familiar, and some were not. All were in rapt attention. The lecture took another twenty minutes. When it was over the volunteers were instructed to stand. None spoke, their hands by their side as they began to march behind the instructor. They walked for a mile or two until they came to a small shed. All was quiet, except for each man’s breath and the whisper of the wind through the hedgerow. Other than the shed there was no sign of human life, only mountains and craggy, stone filled fields, unsuitable for any kind of farming. Each volunteer was given a rifle taken from a wooden box in the corner of the shed. Mick, after first checking the safety and to see if it was loaded, let his hands run over the smooth wooden frame, worn down from being passed down from volunteer to volunteer countless times. He felt history in his hands, the feeling of belonging, being part of something, and the undeniable grace of fighting for a cause that he now truly believed in. He felt connected to these strangers around him. They were his brothers now. Pat looked across at him, his weapon in hand and both brothers smiled. The volunteers broke up into small groups. Mick and Pat were put together along with three other recruits from Donegal. The instructor took each group in turn, going through the basics of firearms and then explosives training. Melissa and the old life back in Derry felt like years ago. Yet she remained as if tattooed inside him.

Pat excelled at weapons training. He was a natural marksman and by the second week was helping to instruct the new recruits, who seemed to come in almost on a daily basis. It was hard to get to know anyone as one day they were training alongside them and the next, they were gone, off to fight the war against the imperialist invaders. They came to know the training camp as ‘Teach Uí Bhraonain’, Irish language for the house of Uí Bhraonain. Mick wondered how many of these camps were dotted across the rugged Donegal landscape, or indeed the whole country, but knew better than to ask. The other volunteers seemed slow to offer any of themselves, perhaps worried about not looking the part or the ever-present obsession of the informer. As a result, Pat and Mick didn’t mix much with the other volunteers as they came and went. It was plain to see during training who each volunteer was and what they might amount to. Some were ungainly and stupid, unfit for anything other than light administrative duties. Others seemed born soldiers, cold and fanatical, infected with hatred the likes of which the boys had never seen before. Under the tutelage of the instructor, this hate was encouraged, nurtured, channeled. It was the vital life-blood of the organization and Mick felt it, felt it spreading like black tar inside him. Only she stopped it. Melissa was his only defense against it.

In the second week of training, after their run up the mountain and weapons drill, Mick saw Bean Uí Bhraonain sitting alone by the fire. Most of the other recruits were in bed, reading through the green book of IRA philosophies or the republican histories they’d been issued. Her old blue eyes flicked up at him and she offered a rock to sit on, worn down by innumerable young republicans in the past.

“Ah, Mick isn’t it?”

“Aye, it is. You can tell me from my brother?”

“You’re the one with the shaggy hair. It’s not too difficult.” She smiled, staring into the heart of the fire. “Your training’s almost finished now?”

“I think so, Bean Uí Bhraonain.”

“Aye, it is.” Her words were slow and deliberate. “You know what you’re fighting for?”

“Aye, I do.”

“There was a bomb outside a pub in Belfast last night. A car bomb was set off. It was a Catholic area and when the civilians outside came out onto the street the snipers that the UVF had set up opened fire. Five civilians killed, including one Prod. The stupid bastards got one of their own. It was the local IRA who showed up to stop them, to fight back. The soldiers showed, sure, but they were working with the loyalists. If it weren't for the IRA, more Catholics would have died.” The orange flames of the fire burned deep in her eyes as she spoke. “Without the IRA, without brave young men like you and your brother, and the rest of these volunteers, the Catholic people of Northern Ireland are defenseless.”

“My father was killed, in Derry, on Bloody Sunday.”

Bean Uí Bhraonain reached into the fire to poke it with a long stick she was holding. “We’ve all suffered at the hands of the British, and because of the traitors in the south who deserted the cause. My father fought in the war of independence, in ’19 along with both my brothers. My father survived, but both brothers died, one at the hands of the Brits, one a

t the hand of the Free Staters. Yes, this war has been going on a long time. I’ve met just about any republican you could care to name, from Michael Collins to Eamon DeVelera to Cathal Goulding and Sean MacStiofain. They were different men, who wanted the same thing, the only thing that can provide justice for the people of Ireland - complete separation from the Imperialist British. There’s no other way. Cold steel, that’s all the Brits and Prods understand. The cold kiss of the bullet.”

Mick nodded but felt outmatched, unable to respond. He stayed silent. Her soft-spoken words shielded a violent, bitter tradition behind them. She’d never known anything else, he thought. She was an inspiration and a warning in one.

“It’s up to you,” she continued. “It’s up to you and the rest of the volunteers, here and throughout this beautiful country to seize this chance that’s arisen to throw out the foreign invaders. They’ve inflicted eight hundred years of misery on the people of this country. If I were thirty years younger, I’d be right beside you.”

The next morning McClean came back, and the boys left with him. Their training was over. They were ready to join their unit, ready for duty.

Their first action as IRA volunteers was a raid on a quarry two weeks later to appropriate Cordtex detonating wire for the cause. They had met Ken Wall at training camp. It had been his idea. His father had worked there until he’d been laid off the year before. The quarry had been unguarded except for one security guard who slept as Pat sliced through the padlock on the shed. Mick had stood back and watched, then helped carry the rolls of detonating wire, precious as gold to an underfunded IRA, back to the van where Ken was waiting for them. McClean was delighted with the proceeds of the raid on the quarry. He didn’t care about the details, and no one felt the need to fill him in.

Mick opened the barbershop again. Being a volunteer in the IRA was not a paid position. Only full-time members were paid, and even then it was no way to make your fortune. Most of the people who came into the barbershop knew who he was now, what he’d become, and he felt the respect that went along with his new station. He was dedicating his life, sacrificing the certainty of the happiness he would have had with Melissa for them. It felt good to be part of something, to stand with his brother in fighting for the rights of their community. But he still pined for her. The feelings inside wouldn’t die. He would sometimes close the doors of the shop at the end of the day and sit down in front of the picture of his father, still hanging exactly as his mother had left it. He found himself speaking to it, even asking questions. He had no one else to talk to about Melissa.

Chapter 12

Melissa finished her makeup, rubbing her little finger across her bottom lip to even out the pink lipstick. The brush ran through her fine brown hair as the T-Rex single wound to an end. She reached across with a deft hand to take it off the record player before it scratched and replaced it with Elton John. It was Friday night in late June. It had been almost two months since she’d seen Michael, and she was trying to throw out the memories of him, to extricate them from her mind. But he had infiltrated every part of her. She had tried to change who he was in her memory. She attempted to remember him as a bad person or to pretend that he hadn’t been good to her, to pretend he hadn’t loved her. It didn’t work. Lying to herself was a waste of energy. The fact that he was in the IRA now was unavoidable. So many of her friends had boyfriends who lied and cheated and abused any trust placed in them, but somehow none of that was worse than what Mick had done, even though she understood why.

The doorbell rang. She was ready. The record ended, and she could hear her mother greeting her cousin downstairs. Melissa evaluated herself one last time in the mirror. She had some doubts about her earrings but forced herself out the door. Melissa’s cousin, Victoria, had promised to bring her out on the town, and not in Londonderry either. She needed to get away. Victoria’s hometown of Limavady, twenty miles away on the Coleraine Road, would have to do. Melissa’s mother kept Victoria at the door for ten minutes before they made their way out toward the car. Victoria didn’t put the headlights on as they drove out of the city, the summer night as bright as the afternoon even at almost nine o’clock.

They drove to Victoria’s house where they dropped off Melissa’s bags and after a quick conversation with her parents, made their way to the pub. Victoria’s friend, Jenny, was waiting for them in The Royal Arms, but she wasn’t alone. Several boys were with her. A tall, handsome boy stepped forward, proffering a hand to Melissa.

“Hello, I’m Clive,” he said, his southern English accent as noticeable as a red apple among the green. He was tall and handsome with black hair and tanned skin. “Can I buy you a drink, miss?”

Victoria stood in between them. “Now, if you’re going to buy my attractive cousin a drink, surely you can get us all one?” Clive smirked and left for the bar. Two minutes later he returned with one drink, which he handed to Melissa. He scanned the expectant eyes on him with a smile before going back to get the drinks he’d bought for everyone else in the group. No one said it, but everyone knew they were soldiers. Soldiers were the only English people around. This was a pub soldiers felt comfortable in. There weren’t many like it in Londonderry.

*****

McClean had told them to expect something that night. It was after ten o’clock and still nothing. Mick came into the kitchen, where his brother was by the phone, cigarette in hand. This was to be their first real operation. They wouldn’t be stealing explosives from any tin huts tonight. They weren’t talking much. The ashtray was almost full. Pat thought about their mother, and the torturous process of reading her last letter. She cried for them every night now, dreaded for their future. It wasn’t too late; she’d written. But it was, Pat knew that. It was too late for him the moment their father had ventured out to help the man crawling along the ground, and those shots ripped through the air. The harsh sound of the phone cut through the silence.

“Hello,” Pat answered.

“I’ll be at your house in ten minutes. I’ll need you both.” He hung up.

Pat replaced the receiver. The silence came again. His brother was looking at him.

“That was McClean. He’ll be here in ten minutes. He needs both of us.” Mick didn’t answer. “You ready for this?”

“I’m ready,” Mick replied.

*****

The English boys were buying the drinks. Victoria was talking to Clive now, but Melissa could see him peeking at her over Victoria’s shoulder. She felt the heat come to her skin as he smiled at her. It didn’t feel right, having these feelings about someone who was probably a soldier, but wasn’t she trying to move on? Not all Catholics, not all Protestants, not all soldiers were the same. Norman and Robert, the two other boys with Clive, were in front of her, and she began the conversation.

“So, where are you from in England?”

“Leeds,” Robert answered. “Me and my little brother here have been over here a few months now,” he put his arm around Norman, who was already swaying from side to side. It was only half past ten.

Norman managed to nod in agreement. “It’s been so bloody hard trying to deal with these Paddys,” he slurred. “We thought we were here to help the buggers, but they don’t want it. At least you people appreciate what we’re trying to do for this god-forsaken place.”

The insult bit at Melissa, but she brushed it off with a smile.

“Forgive my brother,” Robert answered as he clipped Norman over the back of the head. “He’s had a few too many. This is what happens when you let eighteen-year-olds out of the barracks in the middle of a Saturday afternoon for the rest of the night.”

Melissa smiled again, unsure what to feel. Robert had a kind face. It was hard to fathom how someone like him could open fire on innocent people. Was he so different from the soldiers who’d fired on the crowds on Bloody Sunday?

“What’s it like for you over here?”

“It’s a lot of different things,” Robert said, looking directly into her eyes. �

��It’s very boring when we’re not doing anything. We were in Londonderry for a while. The only excitement we ever got was during those bloody riots, getting stones and petrol bombs chucked at us. It must sound strange, but in a way we came almost to look forward to those riots.”

“You looked forward to them?”

“Those riots were the only break in the boredom.”

“What else is it like being here?”

“It's intimidating. There’s a lot of history here that’s nothing to do with us, and we’re here to try to sort it out. Nobody knows what to do. We’re all trying to get through each day as it comes, and get home. I’m going to get married when I finish my tour of duty next year. Do you want to see a picture of my fiancé?”

“Aye, of course, I do.”

Robert took out a brown leather wallet and produced a black and white photo of a girl, about her age hugging a golden retriever. “Her name’s Charlotte,” he said. “I need to write to her; I’ve not written to her yet this week.”

“You do that tomorrow.”

*****

The Bogside Boys

The Bogside Boys